Tobias Zielony

DE

-

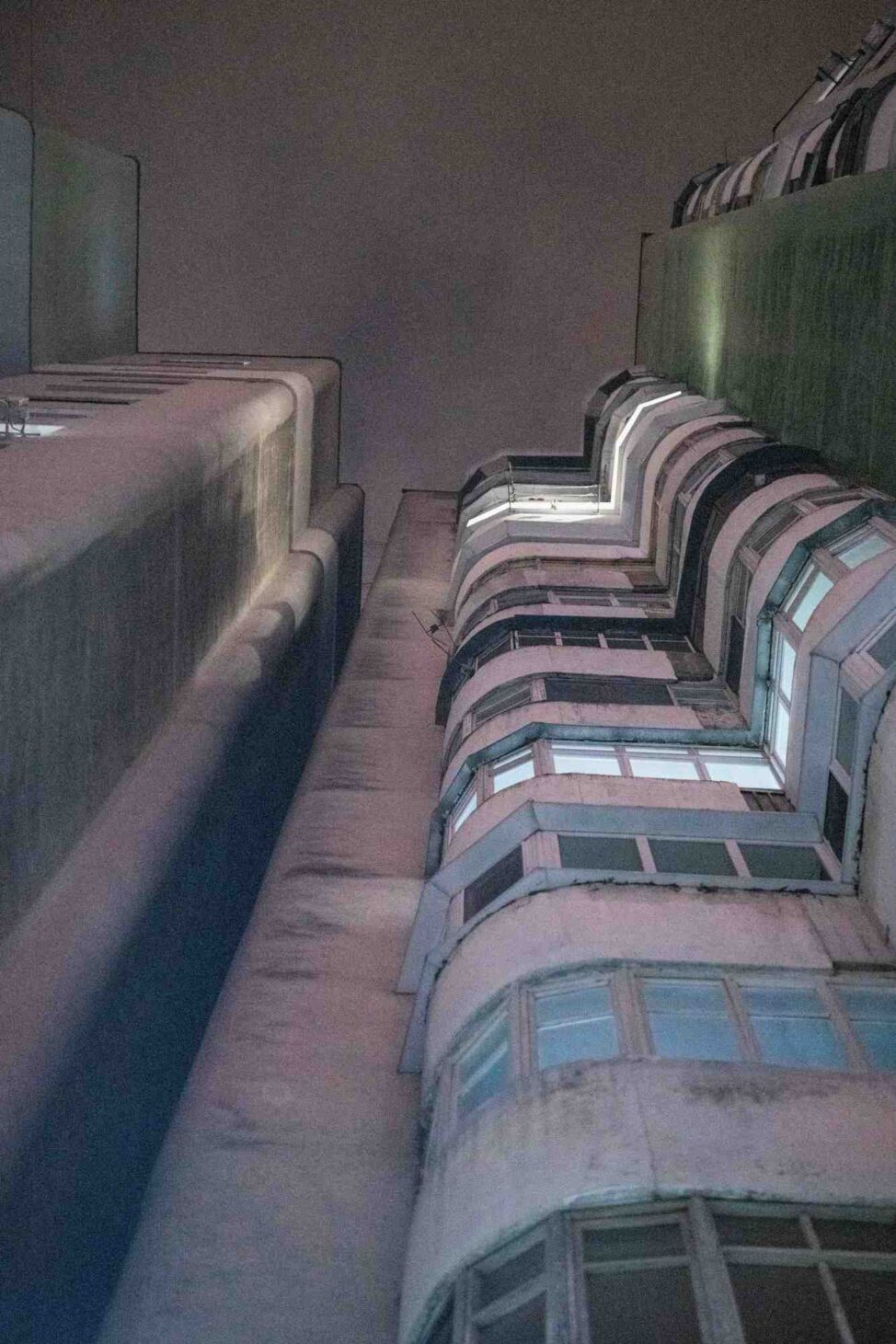

Electricity / Afterimages - 2023 - Photographic series [Detail] -

Electricity / Afterimages - 2023 - Photographic series [Detail]

Tobias Zielony (b. 1973 in Wuppertal) is a German photographer and video artist living in Berlin. In 2015, The Citizen, Zielony’s collaborative work with refugee activists in Germany and African media, represented Germany) at the Venice Biennale and was shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation award.Tobias Zielony (b. 1973 in Wuppertal) is a German photographer and video artist living in Berlin. In 2015, The Citizen, Zielony’s collaborative work with refugee activists in Germany and African media, represented Germany) at the Venice Biennale and was shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation prize.

Electricity / Afterimages, 2023

“I wish photographs could do more. Photography is powerless. I’ve often said this to myself during this war. This powerlessness can be seen even when a photo—similar to a video—depicts crime as its subject.

With extreme restraint, it attempts to imitate news reports, adhering to the genre’s strict rules. But it doesn’t succeed. It reveals itself to be a superfluous witness to violence. Its testimony will be deferred to the future, in order, perhaps, to serve an imagined sense of justice. But in the precise moment in which the photograph is made and shared, it is impotent. Because it cannot halt the events that triggered its making. Testifying to a criminal act in a photograph does not directly lead to justice.

The failure of photography. If photography, which is outpacing other fine-art genres, chiefly seeks to capture the present moment and repeatedly makes this its most salient characteristic, then war exposes how photography fails. War photographs mummify the present instant. An archaic past returns and smuggles itself into present-day life. The gaze captures the moment, classifies it—and relegates it to the past. That makes things easier, more comfortable. Otherwise you would have to take urgent action to stop the events, over which one purportedly has no control. The photographs travel the world, the world abdicates responsibility. The war goes on.

The Russian state failed to wholly destroy Ukraine’s energy infrastructure during their October 2022 attacks, so they waged further attacks shortly thereafter. Air raid sirens send people into cellars and bomb shelters. To conserve energy with an eye to the onset of winter, electricity is regularly switched off in major cities for 8 to 12 hours a day. Ill, weak, and older individuals living on the upper floors of high-rise buildings must remain in their apartments for hours as the air raid sirens sound, because their elevators cannot operate without electricity.

Sacrificing electricity, sacrificing heat. When, later that autumn, the cold sets in, some rooms cannot be adequately heated because the heating systems, as well as the electricity, are being shut off for many hours each day.

I remember walking through the streets of Kyiv on a clear February morning earlier this year, when the electricity was switched off. Such a switch is more audible than visible. Suddenly, the background hum of the power cables disappeared. The city felt changed, transformed. Each familiar noise took on a new, unexpected existence in this unknown stillness. It lasted only a few minutes. Then the diesel generators were switched on and their dogged, productive thrum filled the abrupt absence.

Rays of war. Seen in photographs, the war always appears like a stage for stark contrasts.

The scenes of tragedies are lit to the utmost, but murky, dimmed areas lie just adjacent. Photography is a chemical reaction to the passage of light through a lens and requires energy for its very existence. At the same time, the concentration of photographic attention on an event means that it is capable of summoning energy and resources. Even though this war is being waged at a time when almost everyone has a smartphone with a camera, its map is riddled with gaping dark craters of missing information. These are not the obvious crime scenes but the countless places on the map in which the depressing, melancholy, and horribly quotidian “soft” effects of war may be seen. “Soft,” because this war is ultimately about genocide, with regular attacks on residential areas and the murder of defenseless and unprotected individuals.

The days pass, soundless as dust, each one resembling the next, and somewhere nearby there is fighting, and there is no point in complaining.

Ukraine had to cease exporting electricity to the EU and Moldova on October 11, 2022. From then on, authorities introduced strict electricity rationing measures. There were power outages in Chișinău. Streetlights were turned off at night. Moldova also decided not to purchase any more electricity from the breakaway Russian-controlled region of Transnistria. This decision has since been reversed. Rising energy prices have led to political instability and fear of a Russian military intervention.

The war continues to echo in Tobias Zielony’s photographs of Chișinău. In these snatched islands of life in the shadows, delicate figures show a reality shot through by war. It is a reality about which war photography cannot speak, because it has nothing to say.

In the fog of war, I recognize the marginalized allies—the photographed and the photographer. The actions lie outside the usual field of vision; the figures are solitary and appear placed at random in the cityscape. The photographs do not depict the war. They refrain from articulating the meaning behind the imposed darkness, not due to individual decisions, ecological concerns, or new ways of life, but rather because of forcibly induced deprivation—and yet, this deprivation is a small link in the chain of criminal actions. When I view the people in these photographs, I realize that I, too, am in the gray zone of a hypothetical safety.”

Text: (extract) Yevgenia Belorusets

Wolfen is about a lost dirty icon, and about the distant future. The town of Bitterfeld-Wolfen was home to ORWO-Werke, East Germany’s largest film factory. ORWO’s black-and-white and color films helped define the style of movies and photography throughout the Eastern Bloc. Until the Wall fell. The sprawling plant once employed 15,000 people; now two dozen work here. The rest was liquidated, the factory halls torn down. What is left of the factory manufactures an especially durable archival film designed to preserve analog pictures and digital data in the form of QR codes for over a thousand years. Who, one wonders, will read the information a millennium from now? Extraterrestrials (who speak English)? We see photographs Zielony took on the scene, some on that very long-lasting film. And we read short texts based on Zielony’s conversations with employees who worked in the factory’s darkroom. The plant’s notorious contamination with toxic chemicals, the degrading labor conditions, the dependency on the Soviet Union come up, as do the collapse of the industry and questions of the past and the future, of knowing and ignorance, understanding and incomprehension, light and darkness.